This Day in Black History: November 15th

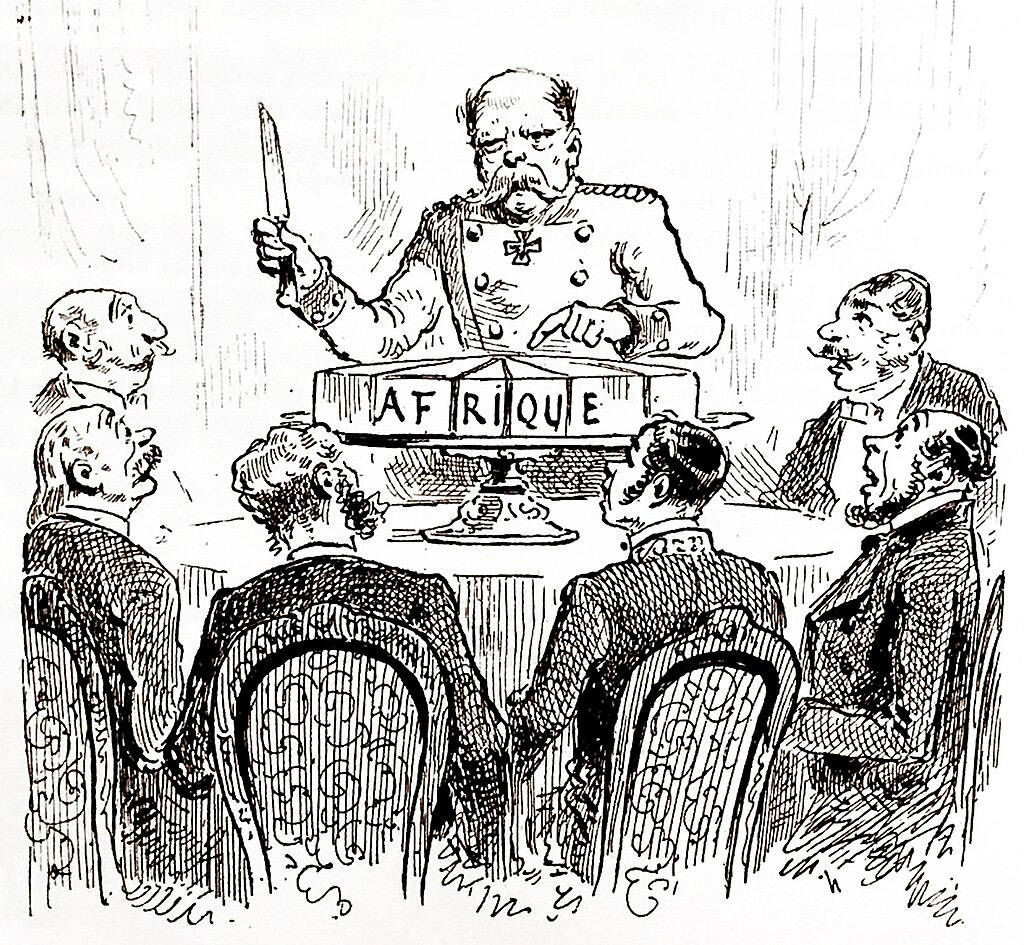

On November 15, 1884, representatives from 14 nations gathered in Berlin to begin a months-long meeting that would shape the future of the African continent. Known as the Berlin Conference, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck convened it at the request of Belgium’s King Leopold II.

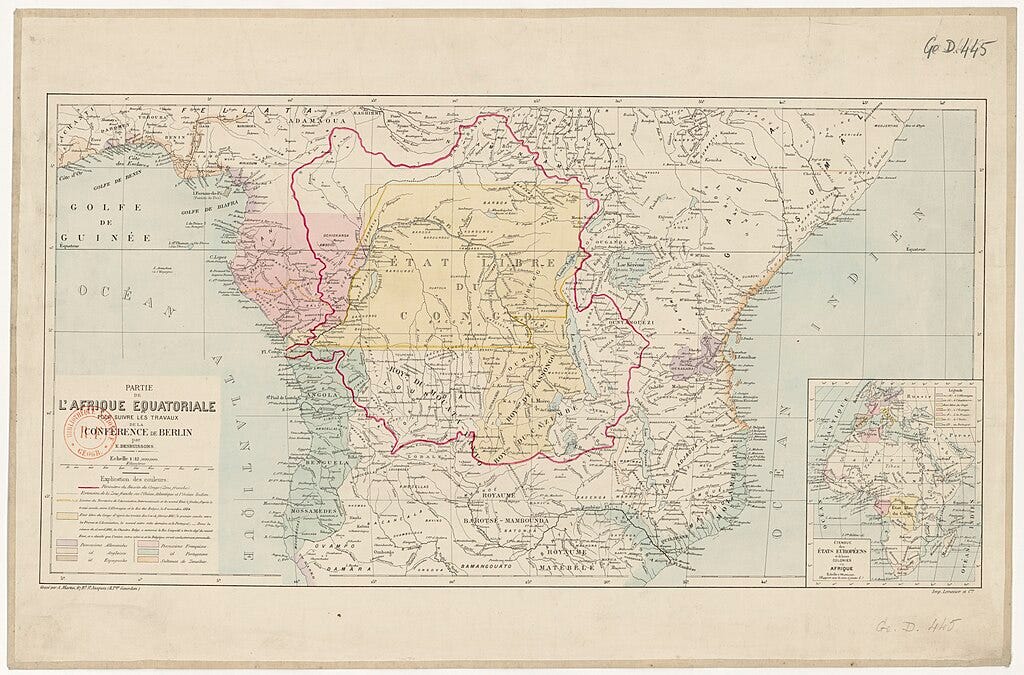

The sessions were held on Berlin’s Wilhelmstrasse and concluded on Feb. 26, 1885, with the signing of the General Act of Berlin. Although European involvement in Africa had already intensified, the conference marked the moment when competing powers formalized their approach to territorial acquisition and trade.

The conference brought together major colonial powers, including Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium and Italy. Seven other nations participated but left without securing any formal African territory. The United States attended but reserved the right to accept or reject the conference’s conclusions.

No African leaders were invited.

The General Act of Berlin aimed to regulate European actions in Africa. It declared the Congo and Niger rivers open to international navigation and established free trade zones in the Congo Basin. Delegates also agreed to notify one another when claiming new territories. A central feature of the act was the principle of effective occupation, which stated that a colonial claim would be recognized only if the occupying power demonstrated an administrative presence, signed treaties with local leaders and maintained order. The stated intention was to curb hollow territorial claims, but in practice, it accelerated European expansion.

Although the conference is often described as the moment Europe carved up Africa, historians note that only the borders of the Congo region were formally established there, and even those were later revised. Many colonial boundaries resulted from bilateral agreements made before and after the conference. Still, the Berlin Conference played a significant role in intensifying the Scramble for Africa. European states moved quickly to secure territory before rivals could do so, motivated in part by growing industrial demand for rubber, minerals, timber and ivory. Africa also offered new markets for European-manufactured goods, reinforcing economic motives for colonization.

Explorers and missionaries helped pave the way for European claims. Figures such as Henry Morton Stanley and Pierre de Brazza negotiated treaties and mapped regions that European governments later used to justify control. Portugal, France and Britain maneuvered for strategic advantage along coasts and inland waterways, while Germany sought to establish itself as a new colonial player.

By the early 20th century, nearly all of Africa was under European rule except for Ethiopia and Liberia.