Thanksgiving at 404: America’s Origin Myth Is Glitching

Today marks the 404th anniversary of Thanksgiving.

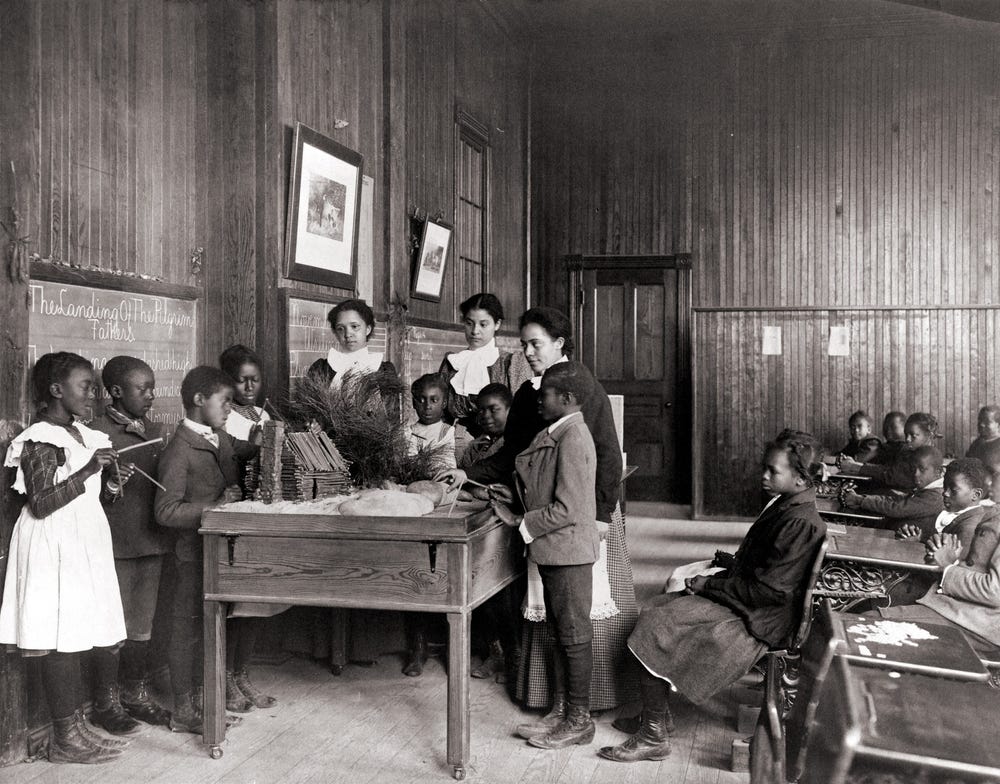

Here are five facts about the American holiday and the Plymouth settlers you might not have learned about at school.

A generation after the “First Thanksgiving,” over 40% of the Wampanoag tribe was killed.

Although leaders of the Native American tribe initially signed a peace treaty, peace between them and the Plymouth settlers was short-lived. Initially, the Wampanoag were hesitant to align themselves with the Mayflower members. Six years prior, members of the tribe were sold into enslavement by Captain Thomas Hunt, an English explorer who participated in an enslavement trade alongside Spain. The Wampanoag were also devastated by a smallpox outbreak that took the lives of 45,000 tribe members.

As a result of both the enslavement and sickness of the population, the tribe was weakened. When threats from another tribe, known as the Narragansett, came, the tribe leader, Ousamequin, decided that the only way to protect his people from being subjected to the Narragansett was to ally himself with the Plymouth settlers, signing a treaty alongside Governor John Carver with the assistance of Tisquantum. The ensuing peace came to an end around 1675 in a war known as King Philip’s War. Ousamequin’s death served as the prelude to the war, beginning a period of tensions between the Wampanoag and the Plymouth settlers. In 1662, Wamsutta, his son and the new leader of the tribe, passed away suddenly during negotiations with the colonists. His brother and new successor, Metacom, claimed that he was murdered using poison. Tensions eventually escalated into the King Philip’s War, a three-year armed conflict that killed nearly half of the Wampanoag and led to the enslavement of thousands of others.

To Native Americans, Thanksgiving is known as “the Day of Mourning.”

Held each fourth Thursday in November (on Thanksgiving), the Day of Mourning draws attention to all the Native American lives that were lost or suffered from European colonialism. One of the most devastating massacres of Native Americans by the hands of Europeans was the Mystic Massacre. Also known as the Pequot Massacre, an estimated 400 to 700 Pequot Native Americans died, including women, children, and the elderly, due to an alliance between the settlers from Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Saybrook and the Narrangansett and Mohegan. Firsthand accounts by colonists, such as Captain John Underhill, estimate that only five Pequot survivors remained. Around 40 Narrangansett members were also injured as the English confused them for Pequot members. After the massacre, those who survived being burned to death or shot at by the colonists were sold into enslavement or forced into other tribes, with their land eventually being taken by the settlers. The event is credited with setting the basis for U.S. policy towards Native Americans.

For some, the first “true” Thanksgiving was held in Florida.

Historians argued that the arrival of Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the ensuing meal with the Timucuans marked the first Thanksgiving. On Sep. 8, 1565, Menéndez de Avilés arrived in what is now known as Florida, claiming the land for God and the country alongside Captain Father Francisco Lopez. Approximately 800 colonists gathered alongside the priest for mass at a makeshift altar. The Timucuans were invited to the event as well, marking what is considered an earlier example of Thanksgiving. Even earlier, in 1564, French Huguenots held a feast alongside the Timucans to celebrate the creation of Fort Caroline. Both events are no longer recognized due to the attack on Fort Caroline by Menéndez de Avilés. Approximately 130 French Huguenots were killed alongside an additional 200 French shipwreck survivors.

In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the date for Thanksgiving.

Known unofficially as “Franksgiving,” the decision to change the date of Thanksgiving first arose in the first year of Roosevelt’s term. As part of his decision, the then-president decided to move Thanksgiving to Nov. 23. The decision was largely unpopular. Only 22 states reportedly adopted the holiday. Roosevelt continued with the proclamation. In 1941, however, he signed a bill into law, officially making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday in November.

Thomas Jefferson was the only president to not approve of Thanksgiving.

Jefferson first denied marking Thanksgiving due to his belief that church and state should be separated. In his belief, by providing support to Thanksgiving, the government would be supporting a state-sponsored religion. Per Jefferson, feasts and the act of giving thanks are ways to express religion and are emblematic of British rule over American colonies. His reasoning, however, was used against him as Federalists claimed he was a “godless” leader. Thanksgiving was once again marked by the fourth U.S. president, James Madison. Jefferson was never able to properly clarify his stance, as he never provided clarity in public. As a result, he developed a reputation for being against Thanksgiving.