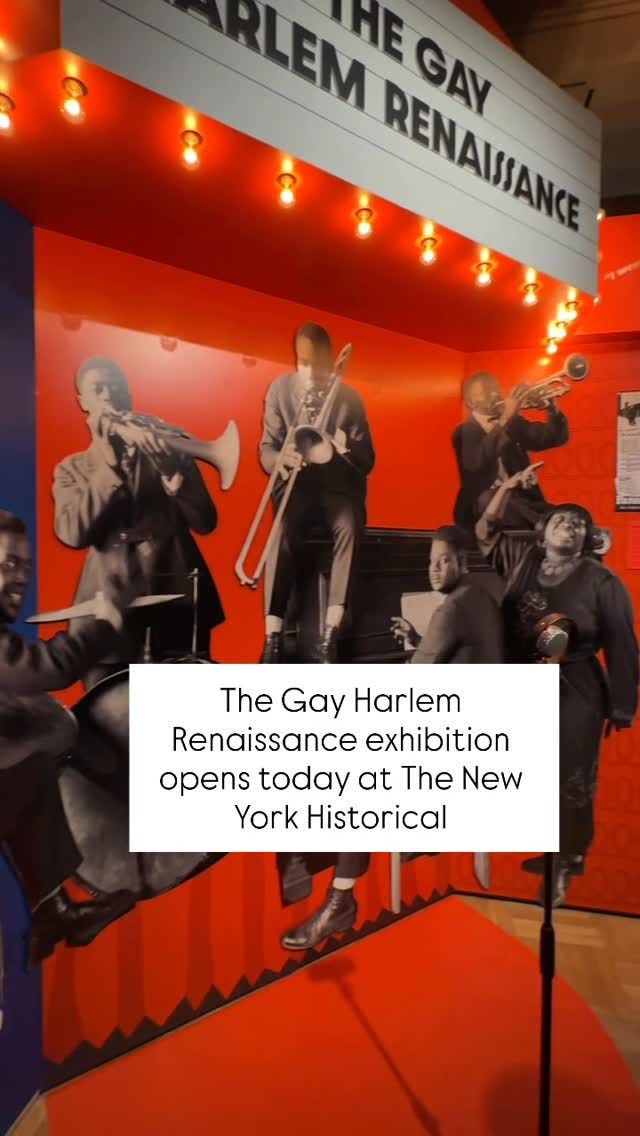

New NYC Exhibit Celebrates LGBTQ Legacy of The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was undeniably one of the most remarkable and celebrated artistic and cultural movements in modern history—and a new exhibit at The New-York Historical Society is highlighting the often-overlooked LGBTQ contributions to this dynamic era.

As Henry Louis Gates Jr. aptly noted, the period was “surely as gay as it was Black,” calling attention to the rich tapestry of creativity that flourished in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s. This period wasn’t just about jazz, poetry and visual arts; it was a celebration of identity, community and expression that paved the way for countless artists and thinkers.

The multi-room exhibition, titled The Gay Harlem Renaissance, which opened on Friday, is an immersive experience that invites visitors to explore a spectacular collection of 200 items, ranging from paintings and sculptures to photographs and books that transport visitors back to the early 20th century of the Great Migration, when Black Southerners sought new opportunities in the North. As it invites you to stroll through the galleries, you’ll encounter the groundbreaking works of literary giants like Alain Locke, Langston Hughes and Bruce Nugent, whose words painted a vivid picture of life during this transformative period.

The experience doesn’t stop there; it delves into the energetic atmosphere of speakeasies, rent parties, drag balls and salons that defined the interwar years, showcasing how creativity thrived in these spaces. Music lovers will appreciate the soulful sounds of iconic entertainers such as Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith, whose performances truly captured the essence of the era.

Allison Robinson, the lead curator of the exhibit, brings a refreshing perspective to the conversation about the movement. She points out that while schools often focused on ethnic groups and social status during those times, sexual orientation and cultural identity were frequently passed over.

“In school, we tend to learn that the Harlem Renaissance was focused on race and class, and the things that they’re producing, but in fact, sexuality and gender are just as important,” she told NBC News.

As Robinson also points out, this was a time when Black artists had a unique opportunity to feature their talents in ways that had never been seen before, allowing them to break free from traditional constraints. But what’s particularly fascinating is the sweeping role Black queer creatives played during this period as well, despite grappling with the dual challenges of racism and homophobia. These artists became a driving force, producing powerful works of art, literature and performance that not only enriched the cultural landscape but also pushed boundaries and challenged societal norms.

Alain Locke, often hailed as the “dean” of the Harlem Renaissance, played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural tapestry of the 1920s with the publication of The New Negro in 1925. This anthology became a cornerstone for the faction, illustrating the powerful voices of Black poets, novelists and artists while promoting a new sense of identity and pride.

Despite being a gay man who remained discreet about his sexuality, Locke was a mentor to some of the era’s most influential figures, including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes and Richard Nugent. Nugent, in particular, garnered attention for his unabashed celebration of beauty and desire, a theme that resonated through his groundbreaking 1926 poem, Smoke, Lilies and Jade. Published in the short-lived magazine Fire!!, the piece candidly expressed his attraction to both men and women, positioning him as a bold voice in Black art. Although Fire!! only lasted for a single issue, it was part of a larger campaign that pushed boundaries and sparked attention that reached far beyond Harlem.

The exhibit pays homage to Drag, a well-known art form of the time, which was prominently on display at Harlem’s annual Hamilton Lodge Ball, the largest and most renowned drag ball on the East Coast.

“By the time you hit the 1920s and ’30s, attendees numbered in the thousands, and they’re coming from up and down the East Coast and as far as Europe to come see the participants perform,” Robinson said.

The celebration became so famous, Robinson said, that it was covered in newspapers around the world and was even written about by Langston Hughes in his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea.

Nightclubs and speakeasies played a vital role in Harlem’s social scene. The exhibit honors these establishments with a large recreation of a Harlem nightlife map, highlighting popular locations that attracted both gay and straight patrons and drew visitors from all over New York City.

One notable venue was Gladys’ Clam House, home to one of the most famous gender-bending performers of the time: Gladys Bentley. Initially called Harry Hansberry’s Clam House, the owner eventually renamed it in honor of Bentley, as Robinson noted, “she’s why people were going.”

Bentley began her career performing at rent parties in private homes before making her way into the Harlem nightclub scene when the Mad House (a nightclub on 133rd St, frequented by LGBTQ performers and audiences) sought a male performer. She proposed to perform in a top hat and tuxedo coat, a look that became her trademark for the rest of her career.

However, her masculine style extended beyond the stage. “This is part of her life,” Robinson stressed. “She’s walking up and down Seventh Avenue with a woman on her arm, dressed in a tuxedo and a top hat.”

Thirteen invitations to rent parties are displayed, with all but one issued by Langston Hughes. The exception is an invitation for a “Sunday matinee” from Lillian Foster, who gave it to dancer Mabel Hampton after they struck up a conversation at a bus stop. The two women became romantic partners for over forty years and Hampton treasured the invitation for the rest of her life.

A’Lelia Walker, a patron of the arts and an ally of the LGBTQ community, hosted gatherings in her Harlem home that served not only as places for celebration but also as hubs for exchanging ideas and fostering collaborations. As the only child of entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, A’Lelia organized salons and parties that brought together hundreds of guests in her apartment and later in a grand townhouse on 136th Street, famously known as the Dark Tower. Her gatherings became safe spaces for Harlem’s queer community, with Hughes referring to her as the “joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s.” The exhibit features correspondence and one of Walker’s fashionable coats from her salon days.

Robinson’s hope for visitors is both inspiring and vital: she wants them to truly grasp the incredible creative energy that surged from the Black LGBTQ community in the 1920s and 1930s. She notes that it’s a time when sexuality and gender were more than just personal experiences; they were hot topics being explored in the heart of the Harlem Renaissance.

She says she looks forward to them realizing, “…that even as the figures here were facing a lot of obstacles, they’re producing things that are beautiful and moving and important.”

The exhibition, The Gay Harlem Renaissance, is on view at The New York Historical Society, located in New York City’s Upper West Side, until March 2026.

For more information, visit nyhistory.org.

By Danielle Bennett.